Soliton Mode Locking

Author: the photonics expert Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta (RP)

Definition: a mechanism for laser mode locking based on soliton pulses

Categories:

Related: solitonssoliton periodmode lockingdispersion compensationKelly sidebandsmode-locked fiber lasers

Page views in 12 months: 1022

DOI: 10.61835/01k Cite the article: BibTex BibLaTex plain textHTML Link to this page! LinkedIn

Content quality and neutrality are maintained according to our editorial policy.

What is Soliton Mode Locking?

For the generation of femtosecond pulses, soliton mode locking is a frequently used technique which exploits soliton effects. It has originally been developed for fiber lasers, where however it is quite limited in terms of pulse energy and duration, and later applied to mode-locked bulk (with quasi-soliton pulses).

Soliton Mode Locking of Fiber Lasers

For true soliton mode locking, one has soliton pulse propagation in the used fibers, where the effects of chromatic dispersion and nonlinearity act together such that overall there is no temporal broadening of the pulses nor any change in their optical spectrum [2]. That balance of effects requires fibers with anomalous chromatic dispersion, which is easily possible e.g. in the 1.5-μm regime and — despite the normal dispersion of silica fibers — also in the 1-μm regime when using photonic crystal fibers with a suitable design. A saturable absorber is only required for starting and stabilizing the mode locking, while the pulse shaping is essentially done by dispersive and nonlinear effects. Alternatively, one may use active mode locking. The obtained pulses can have a nice temporal profile with sech2 shape and hardly any chirp, i.e., with a high pulse quality.

Unfortunately, the performance of soliton mode-locked fiber lasers is very limited. For picosecond pulse durations, the soliton energies of typical single-mode fibers are very small (in the picojoule regime), and thus also the possible output pulse energies. (It is also problematic to operate a laser with an intracavity average power far below the gain saturation power, i.e., only slightly above the laser threshold.) For shorter pulse durations in the femtosecond regime, one could in principle obtain significantly higher pulse energies, but then the soliton period becomes much shorter; once it is too short (particularly for a long laser resonator), the circulating pulse becomes unstable due to too high nonlinear phase shifts per round-trip. Before the pulses get really unstable, one may observe substantial Kelly sidebands in the optical spectrum, i.e., a degradation of pulse quality.

A kind of quasi-soliton mode locking can be realized with an additional strongly dispersive element within the laser resonator, such that the soliton balance is determined by the overall dispersion and nonlinearity per resonator round trip. One may then obtain higher pulse energies, but combined with longer pulse durations.

More sophisticated mode locking techniques for much better performance have been developed for fiber lasers. Typically, they rely on substantially more complicated pulse shaping processes. See the article on mode-locked fiber lasers for more details.

Quasi-Soliton Mode Locking of Bulk Lasers

While the concept of soliton mode locking has serious limitations for fiber lasers, as explained above, it has become very important for solid-state bulk lasers. Here, the total intracavity chromatic dispersion is made anomalous e.g. by inserting a prism pair or dispersive mirrors into the laser resonator. A suitable balance of dispersion and Kerr nonlinearity, quasi-soliton pulses can be obtained; one should first care about an appropriate amount of nonlinearity (see below) and then introduce the required amount of anomalous dispersion for dispersion compensation. Because the dispersion and nonlinearity are not smoothly distributed in the resonator, but lumped at certain places (e.g., the laser crystal and dispersive mirrors or a prism pair), one does not obtain true soliton pulses, but quasi-soliton pulses, where the balance of dispersion and nonlinearity holds only for the overall nonlinear and dispersive phase shifts per resonator round trip. Such a balance works if those phase shifts per round trip are not too strong. Again, a saturable absorber is required for starting and stabilizing the mode locking, but the pulse duration may be much shorter than the response time of the absorber.

The quasi-soliton condition implies certain scaling laws for soliton mode-locked lasers. For example, quadrupling the chromatic dispersion in the laser resonator allows the pulse energy to be doubled, while the pulse duration is also doubled, so that the peak power and thus also the nonlinear phase shift per round trip remains unchanged.

Compared with the regime of mode locking with near-zero chromatic dispersion in the laser resonator, soliton mode locking allows for substantially stronger nonlinear phase shifts due to the Kerr nonlinearity, which would otherwise make the pulses unstable. The optimum nonlinear phase shift per resonator round trip is normally between some tens and a few hundred milliradians:

- Too low values of the nonlinear phase shift lead to rather weak soliton pulse shaping and consequently a stronger sensitivity to other influences, such as pulse shaping details of the saturable absorber, the limited gain bandwidth, etc. This can happen for mode-locked solid-state bulk lasers operating with relatively long pulses; in that regime, one also often requires inconveniently large amounts of anomalous intracavity dispersion.

- On the other hand, too strong nonlinear phase shifts can make the pulses unstable due to the periodic disturbance of the circulating pulse on a length scale which is not much shorter than the soliton period.

In some cases, the intracavity chromatic dispersion can be tuned e.g. by modifying the insertion of prisms of a prism pair. One may then observe a regime where the pulse duration (for fixed pump power and pulse energy) varies in proportion to the overall amount of anomalous dispersion. However, when the pulse duration gets too short, the pulses suddenly become unstable. The minimum possible pulse duration can be set by the limited gain bandwidth or by too high nonlinear phase shifts. As an example, Figure 1 shows how the pulse duration varies with the amount of chromatic dispersion in such a laser as numerically modeled with pulse propagation software. The dependence is nearly linear for sufficiently strong chromatic dispersion, but the pulses become unstable if the dispersion becomes too weak.

For too low dispersion, the pulses are unstable; therefore, the corresponding markers are missing in the diagram. The simulation was done with the RP ProPulse software; see the case study.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the optical spectrum within thousands of round trips in the unstable regime (GDD = −400 fs2):

For mode-locked bulk lasers, soliton mode locking usually works best for pulse durations below 1 ps. For pulse durations well above 1 ps, impractically large amounts of anomalous dispersion and also possibly elements for an enhanced total nonlinearity would be required. Only for pulse durations below 10 fs, nonlinear phase shifts usually become so strong (despite the use of a rather short laser crystal) that the stability of the circulating solitons requires a very strong saturable absorber.

When used in the appropriate regime of nonlinear phase shifts, soliton mode locking of bulk lasers normally allows for good performance combined with high stability and very high pulse quality, i.e. for well-shaped, nearly bandwidth-limited ultrashort pulses with low chirp. Due to the relatively simple pulse shaping mechanism, such lasers can often be designed mostly based on simple analytical equations, not necessarily requiring numerical pulse propagation studies — except perhaps if additional details such as the detailed dependence of stability on design details need to be studied for obtaining cutting-edge performance.

Frequently Asked Questions

This FAQ section was generated with AI based on the article content and has been reviewed by the article’s author (RP).

What is soliton mode locking?

Soliton mode locking is a technique for generating ultrashort pulses by exploiting soliton effects. It works by creating a balance between anomalous chromatic dispersion and Kerr nonlinearity, which together prevent the temporal broadening of the pulses.

How does soliton mode locking differ between fiber and bulk lasers?

In fiber lasers, one can have true soliton propagation, but this is limited to low pulse energies. In bulk lasers, one achieves quasi-soliton mode locking, where lumped dispersion and nonlinearity are balanced on average per round trip, allowing for higher performance and stability.

What is a quasi-soliton pulse?

A quasi-soliton pulse is formed in a laser where dispersion and nonlinearity are not distributed uniformly but are lumped in separate components. The balance between these effects holds only for the overall phase shifts per resonator round trip.

What determines the pulse duration in a soliton mode-locked laser?

The pulse duration is roughly proportional to the total amount of anomalous dispersion in the laser resonator. The minimum achievable duration is often limited by the laser's gain bandwidth or by instabilities caused by excessive nonlinear phase shifts.

Why is a saturable absorber necessary for soliton mode locking?

While the main pulse shaping is done by the balance of dispersion and nonlinearity, a saturable absorber is required to initiate the mode-locking process and to stabilize the resulting pulse train against noise.

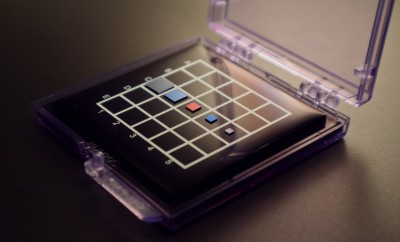

Suppliers

Sponsored content: The RP Photonics Buyer's Guide contains ten suppliers for mode locking. Among them:

Electro-optic phase or intensity modulators including a driver can be used at frequencies up to 100 MHz for actively mode-locking lasers at various wavelengths. These are manufactured on customer’s demand.

Proprietary electro-optic deflectors (EOD) are also offered as efficient active mode-locking devices.

Our customized semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAMs) can be used for passive mode-locking of fiber, solid-state and semiconductor lasers, with wavelengths ranging from 620 nm to 3.5 µm.

Contact us for the optimal customized SESAM for your application.

Bibliography

| [1] | L. F. Mollenauer and R. H. Stolen, “Soliton laser”, Opt. Lett. 9 (1), 13 (1984); doi:10.1364/OL.9.000013 |

| [2] | F. M. Mitschke and L. F. Mollenauer, “Ultrashort pulses from the soliton laser”, Opt. Lett. 12 (6), 407 (1987); doi:10.1364/OL.12.000407 |

| [3] | J. D. Kafka et al., “Mode-locked erbium-doped fiber laser with soliton pulse shaping”, Opt. Lett. 14 (22), 1269 (1989); doi:10.1364/OL.14.001269 |

| [4] | I. N. Duling III, “All-fiber ring soliton laser mode locked with a nonlinear mirror”, Opt. Lett. 16 (8), 539 (1991); doi:10.1364/OL.16.000539 |

| [5] | T. Brabec et al., “Mode locking in solitary lasers”, Opt. Lett. 16 (24), 1961 (1991); doi:10.1364/OL.16.001961 |

| [6] | K. Tamura et al., “Soliton versus nonsoliton operation of fiber ring lasers”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 64, 149 (1994); doi:10.1063/1.111547 |

| [7] | F. X. Kärtner et al., “Stabilization of solitonlike pulses with a slow saturable absorber”, Opt. Lett. 20 (1), 16 (1995); doi:10.1364/OL.20.000016 |

| [8] | F. X. Kärtner et al., “Solitary pulse stabilization and shortening in actively mode-locked lasers”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 12 (3), 486 (1995); doi:10.1364/JOSAB.12.000486 |

| [9] | M. E. Fermann et al., “High-power soliton fiber laser based on pulse width control with chirped fiber Bragg gratings”, Opt. Lett. 20 (2), 172 (1995); doi:10.1364/OL.20.000172 |

| [10] | F. X. Kärtner et al., “Soliton mode-locking with saturable absorbers”, J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2 (3), 540 (1996); doi:10.1109/2944.571754 |

| [11] | A. B. Grudinin and S. Gray, “Passive harmonic mode locking in soliton fiber lasers”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14 (1), 144 (1997); doi:10.1364/JOSAB.14.000144 |

| [12] | M. Santagiustina, “Third-order dispersion radiation in solid-state solitary lasers”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14 (6), 1484 (1997); doi:10.1364/JOSAB.14.001484 |

| [13] | R. Paschotta et al.,“Passive mode locking with slow saturable absorbers”, Appl. Phys. B 73 (7), 653 (2001); doi:10.1007/s003400100726 |

| [14] | A. F. J. Runge et al., “The pure-quartic soliton laser”, Nature Photonics 14, 492 (2020); doi:10.1038/s41566-020-0629-6 |

(Suggest additional literature!)